INTRODUCTION

Violence is a global public health problem with consequences for the physical and mental development of those exposed to it. Adolescents exposed to contextual violence tend to experience challenges in their individual development such as interpersonal and social relationships, due to its physical and mental implications (Martín del Campo-Ríos & Cruz-Torres, 2020; Organización Mundial de la Salud, 2006). In addition, interpersonal violence at the family level can manifest through physical, sexual, and psychological violence, and neglect, (Organización Mundial de la Salud, 2006), also affecting the development of adolescents. Adolescents exposed to any of these types of violence tend to drop out of school, exhibit problematic behaviors, engage in substance use, and are at a higher risk of developing a wide array of mental disorders (Noriega Ruiz & Noriega Saravia, 2021). Recently, violence exerted through digital social media has been associated with depression, suicide and other mental health conditions among adolescents (Álvarez Gutiérrez & Castillo Koschnick, 2019).

As a result of COVID-19, an increase in intrafamily violence was reported, especially towards women, children and adolescents (Marques et al., 2020). Among the main risk factors found for this increase were the use of substances by the perpetrators, and work overload in women, which decreases the ability to avoid conflict (Alt et al., 2021; Holmes et al., 2020; Marques et al., 2020). In some Latin American countries, adolescents reported an increase in arguments at home (21%) (UNICEF, 2021), stress (52%), and episodes of anxiety (47%) (Naciones Unidas, 2021). In addition, there were increased reports of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress, (Caffo et al., 2021; Rauschenberg et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2020a) due to the mitigation measures for COVID-19 (SEGOB, 2020). Among adolescents, the most common disorder reported during lockdown was depression (González Rodríguez & Martínez Rubio, 2022). Studies before the pandemic associated exposure to violence with an increase in the probability of developing depression (Orozco Henao et al., 2020; Ughasoro et al., 2022)an increased risk of suicide, (Rossi et al., 2020) dropping out of school, victimization, substance abuse, (Benjet et al., 2013) and perpetration of violence (Kim et al., 2021). The latter was exacerbated as a result of the change in the personal, familial and social dynamics caused by COVID-19 (Gómez Macfarland & Sánchez Ramírez, 2020).

In Mexico, the prevalence of depression in the adolescent population increased from 13.6% in 2018 to 19.7% in 2020 (Shamah-Levy, 2021; Shamah-Levy, 2020). During the pandemic, 36.5% of adolescents between the ages of 15 and 17 reported having experienced some type of violence at home (Larrea-schiavon et al., 2021). These results showed that the prevalence for all types of violence was higher in girls than boys; 20.2% of girls and 19.9% of boys reported physical violence; 30.4% of boys and 38.9% of girls reported psychological violence; 1.1% and 3.6% of boys and girls reported sexual violence; while 43.5% of girls reported some type of online harassment compared to 24.3% of boys (Larrea-schiavon et al., 2021). Previous studies have found that some of the factors associated with being victims of violence among adolescents are being female, directly witnessing violence, and low socioeconomic status (Martín del Campo-Ríos & Cruz-Torres, 2020; Noriega Ruiz & Noriega Saravia, 2021).

Jalisco is a Mexican state where adolescents (ages 15-19) account for 28.2% of the total population, making it one of the states with the highest proportion of adolescents (UNFPA et al.,2021). Before the pandemic, 60.6% of girls and women between the ages of 15 and 29 reported having suffered some type of violence (UNFPA et al., 2021; Suarez & Menkes, 2006). In 2022, it was among the top ten states with the most femicides and reports of family violence (Secretariado Ejecutivo del Sistema Nacional de Seguridad Pública, 2022). In a study conducted of adolescents from Ciudad Guzmán, Jalisco, 5.0% reported family violence and 12.1% severe depression (Díaz-Andrade et al., 2022) revealing the extent of this problem. The present manuscript hypothesizes that violence experienced and depressive symptoms in adolescents may be associated with sociodemographic factors (such as sex, age and job), family, use of video games and social media. This study seeks to analyze the factors associated with the types of interpersonal violence experienced and depression symptoms in adolescents attending school in the south of Jalisco, in the context of COVID-19.

METHOD

Design and study population

Data are drawn from the Mental Health, Addictions and Violence Survey-Jalisco (Spanish acronym ESMAV), administered to middle (n = 51 schools) and high school (n = 19 schools) students from 16 municipalities in southern Jalisco. ESMAV is a cross-sectional study conducted from September to December 2021. The questionnaire was administered online at the schools, with students answering it on their own computers or cell phones. A total of n = 3,215 students were invited to participate, of whom 126 and 43 failed to meet the age criteria (< 12 or )( 19 years). The final analytical sample consisted of n = 3,046 adolescents ages 12 to 19.

Measurements

Violence. We collected information on five types of violence experienced in the past 12 months: 1. Physical violence: a) have you had any type of object such as shoes, kitchen utensils, or furniture thrown at you, whether or not it hit you? b) have you been slapped anywhere on your body? c) have you been burned with an iron, the stove, a match or cigarette or any liquid or another hot object on your body? 2. Psychological violence: a) has anyone referred to you with rude or aggressive words that have made you feel bad? b) have you had been made fun of due to your physical characteristics, or your knowledge, or your way of thinking, acting and feeling? c) have you been humiliated?; 3. Sexual violence: a) have you been sexually harassed or forced to let yourself be touched or caressed against your will? b) have you been forced to have sexual intercourse against your will, without or with the use of physical force?; 4. Neglect: a) have you been tied you up to prevent you from going out or doing what you want to do? b) have you have been prevented from going to the doctor or had your state or health condition neglected when you needed care? c) have your diet, clothing, recreation or education been restricted at home? d) have you been properly taken care of? 5. Digital violence: a) have you received any type of violence or harassment through the internet/digital social media? Answering “yes” to any of the questions, except for “have you been properly taken care of ?” was regarded as having experienced violence.

Depression. We assessed depression symptoms using The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-IA), validated (α = .92) in Mexican adolescents (Beltrán et al., 2012). BDI-IA includes 21 items on depression symptoms in the two weeks prior to the survey, with four response options. The score ranges from 0 to 63, with higher scores meaning greater severity. The cut-off point used to discriminate between those who presented with depressive symptoms and those who did not, adjusted for gender, is 14 points in boys and 18 in girls.

Covariates: We obtained sociodemographic information on sex, age (categorized as 12-14 years and 15-19 years); grade point average (< 8.0, 8-9, 9-10) being employed (Yes/No); frequency of social media use (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, TikTok, WhatsApp, Twitch) in the past month (never/rarely /occasional/frequent/very frequent); and hours of daily use of videogames (I don’t play/ < 1 hour 1 to ≥ 5 hours per day) (Barrientos-Gutierrez et al., 2019). Parents’ educational attainment was included (complete secondary school or less/complete or incomplete high school/college degree or more/Doesn’t know/Doesn’t have a father/mother). Wealth was measured with the Family Affluence Scale (FAS) (Pérez et al., 2021), an index comprising four items: a) how many cars or vans does your family own? (0/1/2 or more), b) do you have a room to yourself? (0/1), c) during the past 12 months, how many times did you go on vacation with your family? (0/1/2/3 or more), and d) how many computers does your family have? (0/1/2/3 or more), with scores ranging from 0 to 9. Higher scores indicate greater family wealth, with scores being classified into three categories: low (0–2 points), medium (3–5 points), and high (6–9 points).

Statistical analysis

A descriptive analysis was performed to calculate the percentages for each of the categorical variables. Separate Bivariate (OR) and multivariate logistic regression models (aOR) were fitted. First, we explored whether experiencing any type of violence was associated with depression symptoms and any other of the sociodemographic variables. A second set of logistic regression models were fitted to determine the association between experiencing any of the five types of violence and depression symptoms and all the sociodemographic and family variables, including experiencing each of the five types of violence. Analyses were performed using Stata v.15 software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). (Stata Statistical Software: Release 14; Stata Corp., 2017).

Ethical considerations

Informed consent and assent were requested prior to data collection. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee and Research Committee of Health Region VI of Ciudad Guzmán (103/RVI/2021).

RESULTS

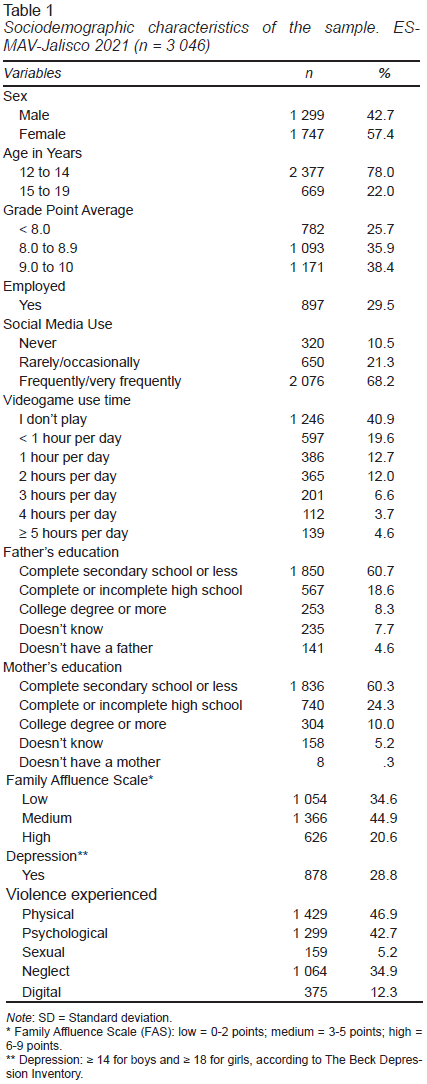

In our sample, 57.4% were girls and 78.0% were ages 12-14. Results show a prevalence of 28.8% of depression, 46.9% reported physical violence, 42.7% psychological violence, 34.9% neglect, 12.3% digital violence and 5.2% sexual violence (Table 1).

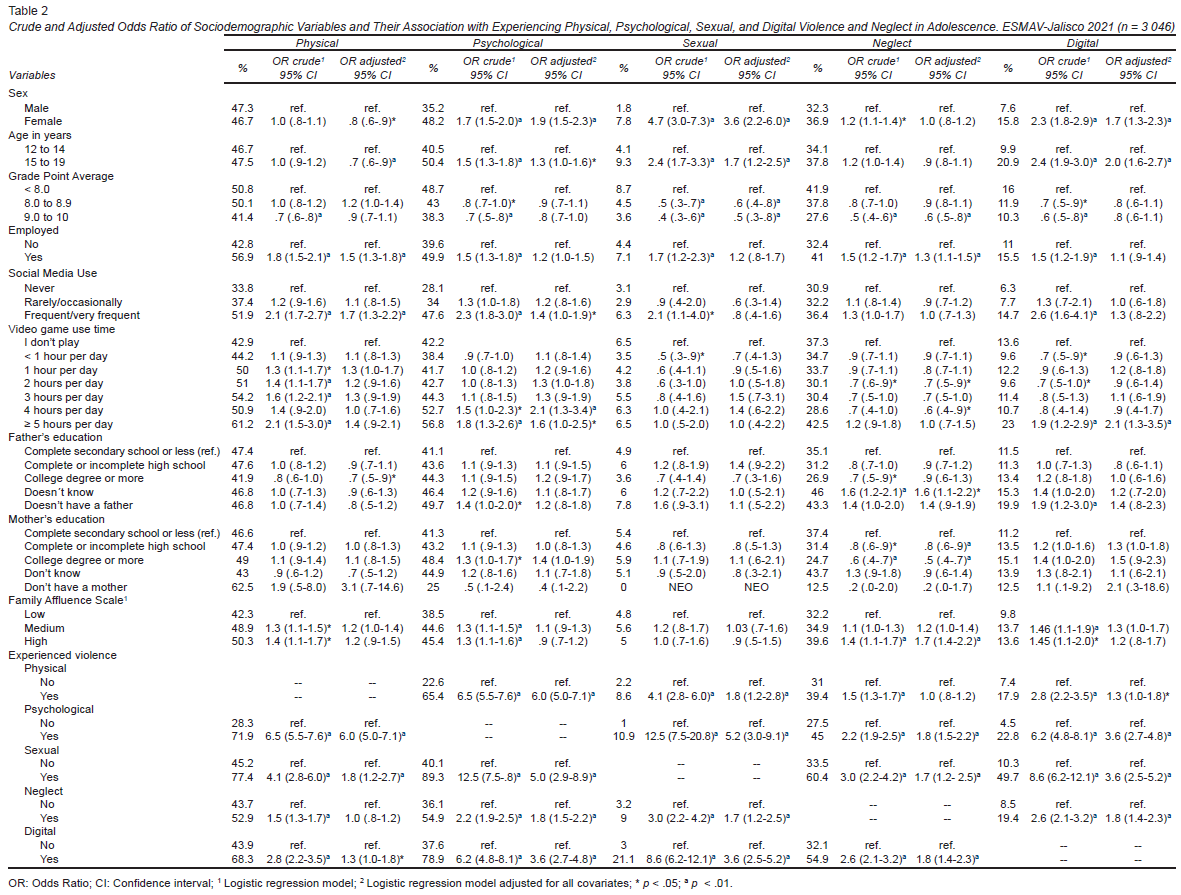

The factors associated with higher odds of physical violence were being employed (aOR = 1.5 95% CI [1.3-1.8]) and frequent/very frequent use of social media (aOR = 1.7 95% CI [1.3-2.2]). Conversely, being a girl (aOR = .8 95% CI [.6-.9]), being 15-19 rather than 12-14 years old (aOR = .7 95% CI [.6-.9]) and having a father with a bachelor’s degree or more (aOR = .7 95% CI [.5-.9]) were associated with lower odds of experiencing physical violence (Table 2).

Higher odds of psychological violence were associated with being a girl (aOR = 1.9 95% CI [1.5-2.3]), being 15-19 years old (aOR = 1.3 95% CI [1.0-1.6]), frequent/very frequent use of social media (aOR = 1.4 95% CI [1.0-1.9]), using video games four hours a day (aOR = 2.1 95% CI [1.3-3.4]) and ≥ 5 hours a day (aOR = 1.6 95% CI [1.0-2.5]) (Table 2).

Higher odds of sexual violence were associated with being a girl (aOR = 3.6 95% CI [2.2-6]) and being 15-19 years old (aOR = 1.7 95% CI [1.2-2.5]). Those with a higher grade point average (aOR = .5 95% CI [.3-.8]) were less likely to experience sexual violence (Table 2).

Violence due to neglect was higher among those who reported being employed (aOR = 1.3 95% CI [1.1-1.5]), adolescents who did not know their father’s educational attainment (aOR = 1.6 95% CI [1.1-2.2]), and those who belonged to the highest tercile of the FAS (aOR = 1.7 95% CI [1.4-2.2]). However, those with a high grade point average (aOR = .6 95% CI [.5-.8]) and a mother with at least a high school education (aOR = .5 95% CI [.4-.7]) were less likely to report dropping out. Being a girl (aOR = 1.7 95% CI [1.3-2.3]), being aged between 15 and 19 (aOR = 2.0 95% CI [1.6-2.7]) and using video games ≥ 5 hours a day (aOR = 2.1 95% CI [1.3-3.5]) were associated with higher odds of digital violence (Table 2).

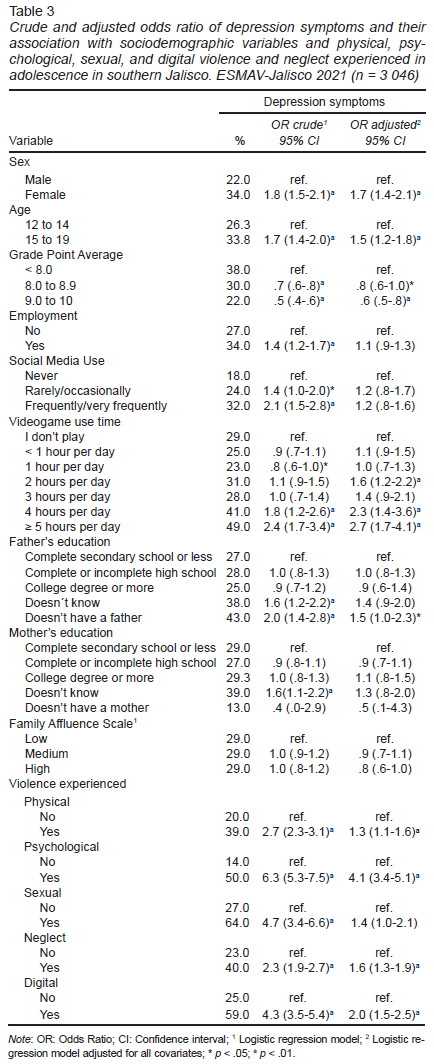

Being a girl (aOR = 1.7 95% CI [1.4-2.1]), being 15-19 years old (aOR = 1.5 95% CI [1.2-1.8]), not having a father (aOR = 1.54 95% CI [1.03-2.33]) and using video games ≥ 5 hours per day (aOR = 2.7 95% CI [1.7-4.1]), were associated with greater odds of depression symptoms (Table 3). Physical (aOR = 1.3 95% CI [1.1-1.6]), psychological (aOR = 4.1 95% CI [3.4-5.1]), and digital violence (aOR = 2 95% CI [1.5-2.5]) and neglect (aOR = 1.6 95% CI [1.3-1.9]) were associated with higher odds of depression symptoms (Table 3).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The results of this study show the factors associated with violence and depression symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic among the adolescent population of southern Jalisco. Experiencing any kind of violence of any type increases the possibility of having depressive symptoms. Likewise, the odds of having depression symptoms were associated with being female, being aged between 15 and 19 years old, poor school performance, and greater use of social media and videogames.

We found a higher prevalence of physical (47.0%), psychological (42.7%) and sexual violence (5.2%) than another study (Larrea-schiavon et al., 2021) conducted of Mexican adolescents in the same year. That study reported that 20.3% suffered physical, 35.0% psychological and 2.6% sexual violence. Online bullying was almost three times higher than what was reported in our study as digital violence (12.3% vs. 34.4%). An explanation for the differences between these studies could be the age range of the participants (12-19 vs. 15-18) or the way the question was framed (have you experienced online harassment?). Likewise, virtual education increased the time spent using the internet, which could have meant greater exposure to digital violence (Armitage, 2021). Our results showed that frequent and very frequent use of social media and videogames increased the probability of experiencing physical, psychological and digital violence, especially among girls, and adolescents aged between 15 and 19 years, as has been reported in other studies (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía [INEGI], 2021; Quispe et al., 2021).

Prior to the pandemic, various studies reported that for some women and their children, the home was the most dangerous place to be (ONU Mujeres, 2020; UNICEF México, 2020) while during the pandemic, several countries reported that violence against women increased, which was reflected in the number of calls to helplines and the demand for shelters, which were filled to capacity (Mlambo-Ngcuka, 2020). Factors such as increased stress, financial and food insecurity, unemployment, and restrictions on movement contributed to the increase in levels of domestic violence (Chandan et al., 2020; World Health Organization, 2020).

Our results show that adolescents with jobs experienced more physical violence and perceived that they were neglected. Due to the nature of this study, it is impossible to tell whether they sought employment after being subjected to physical violence, or whether being employed exposed them to this type of violence. However, child labor has been considered a risk factor for violence and a violation of the rights of children and adolescents, since it can prevent their physical and mental development, becoming a risk factor in their adult lives (Nova Melle, 2008). Various studies (Holt et al., 2008; Renner & Slack, 2006) state that experiencing physical violence at early stages of life has lasting effects on mental health, drug and alcohol misuse (especially in women), risky sexual behavior, obesity and criminal behavior, that persist into adulthood. Children and adolescents who do so are also at risk of reproducing abuse and other types of violence when they are adults. Neglect is at least as harmful as physical or sexual violence in the long term, but has received less scientific and public attention (Gilbert et al., 2009; Pérez Candás et al., 2018).

Neglect was also associated with not knowing the father’s educational attainment and belonging to the highest tercile of the FAS. However, participants with a high grade point average and mothers with a high school education were less likely to report neglect. It is possible that heads of households with higher incomes spend more time away from home, which in turn causes adolescent to feel abandoned and to regard this absence as a failure to appropriately take care of their needs (Lopes da Rocha, 2002). Conversely, when the mother is the primary caregiver and has higher educational attainment, she can make better decisions about the care and mental well-being of the child (Arroyo-Borrell et al., 2017). This finding about family factors is related to care, attention and the establishment of discipline. In addition, the absence of family supervision or the weakening of parental authority combined with violence as a form of communication in the family, are contributing factors to mental health disorders in the adolescent population (Rozemberg et al., 2014). Given the mental health impact and social consequences of neglect on adolescents, more research should be conducted on this issue. A systematic review (Haslam & Taylor, 2022) shows that neglect increases the risk of involvement in gangs and relationships with risky peers, which increases the social violence experienced in Mexico.

The prevalence of depression was similar to that reported prior to the pandemic. In our sample, three out of ten adolescents reported suffering from depression at the time of the survey, with systematic reviews reporting a global prevalence of 25% (González Rodríguez & Martínez Rubio, 2022). A previous study conducted of adolescents from Ciudad Guzmán, Jalisco, prior to the pandemic, (Díaz-Andrade et al., 2022) reported 25.4% with moderate depression. Other studies (Maciel-Saldierna et al., 2022; Vásquez, 2013) of schoolchildren from Jalisco report a difference in depression by sex. As has already been studied, violence can have repercussions on the loss of motivation, joy, the ability to create, to innovate, and even the desire to live (Quirós, 2007).

Studies conducted Mexico suggest that adolescent girls are more prone to family violence (Cerecero-García et al., 2020). The adolescent girls in our study were more likely to experience psychological, sexual, and digital violence than boys, as has been reported in the statistics on violence against children and adolescent women in Mexico (Álvarez Gutiérrez & Castillo Koschnick, 2019). The state of constant alertness and vigilance in the face of imminent danger experienced by female victims of violence has direct consequences at the individual, family, and community level, hence the need to deepen the analysis in a broader context.

Depression was 1.67 times more likely among adolescent girls than boys, as in other countries (Zhou et al., 2020b). These data highlight the inequality between men and women in Jalisco (Instituto Jalisciense de las Mujeres, 2015). However, it could be that women report more because it is more socially acceptable for women to talk about their feelings than it is for men. Likewise, the fact that women tend to report more emotional or psychological disorders compared to men could be due to social and economic disadvantages as other studies have reported (Gaviria Arbelaez, 2009). Among the main factors associated with depression (Duan et al., 2020; González Rodríguez & Martínez Rubio, 2022; Panchal et al., 2023) are being between 15 and 19 years old, using social media more than five hours a day and working during the pandemic. These factors reflect the prevention measures implemented during this period. The greater use of social media as a means of communication and for school activities may have hindered face-to-face interpersonal relationships, affecting all areas of adolescents’ lives, at a time when socialization with their peers is crucial (Meherali et al., 2021).

This study has certain limitations. First, our sample was drawn from schools in a region of Jalisco, meaning that results cannot be generalized to the general adolescent population. However, it provides relevant information on the factors analyzed. Violence is considered a sensitive topic, which could lead to the underreporting of data because it takes place in the family environment. However, the presence of underreporting would only lend further credence to our results. Finally, The Beck Questionnaire is a long instrument and could tire participants, causing them to answer without thinking. However, the instrument is used with and has been validated in the adolescent population (Beltrán et al., 2012).

Violence is a public health problem that should be addressed at early stages of life to guarantee the safe development of the population. The lockdown experienced during the pandemic impacted the interpersonal relationships of the adolescent population, exacerbating violence, evidencing depression problems, more frequently in girls, placing them at greater risk of experiencing depression and various types of violence. Given that the adolescent population has different risk factors, it is vital to implement specific interventions with a gender perspective to guarantee the protection of life with dignity and free of violence for adolescents.

It is also essential to adopt intersectoral social intervention strategies. We consider it necessary to address violence and depression through alliances with various social and institutional sectors (such as the education and health systems, and families) and to be able to guarantee the exercise of human rights. At the same time, the educational model for discipline or parenting within families in the south of Jalisco must guarantee the protection of life with dignity and without violence.