Salud mental 2025;

ISSN: 0185-3325

DOI: 10.17711/SM.0185-3325.2025.034

Received: 27 May 2024

Accepted: 20 November 2024

Family-based Association Study of 5-HTTLPR/SLC6A4 and uVNTR/MAOA Polymorphisms in Patients with a History of Suicide Attempts

Emmanuel Sarmiento-Hernández1 , Ana Fresán-Orellana2 , Beatriz Camarena-Medellin2 , Marco Antonio Sanabrais-Jiménez2 , Sandra Hernández-Muñoz4 , Alejandro Aguilar-García2 , José Carlos Medina-Rodríguez3

1 Dirección de Enseñanza. Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz. Ciudad de México, México.

2 Subdirección de Investigaciones Clínicas. Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz. Ciudad de México, México.

3 Unidad de Fomento a la Investigación. Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz. Ciudad de México, México.

4 Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Unidad Xochimilco. Ciudad de México, México.

Correspondence: Beatriz Camarena Medellín. Subdirección de Investigaciones Clínicas. Departamento de Farmacogenética, Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz. Calzada México-Xochimilco No 101, Col. San Lorenzo Huipulco, C.P. 14080, Alcaldía Tlalpan, Ciudad de México, México. Email: camare@inprf.gob.mx

Abstract:

Introduction: Biological factors, especially genetic ones, are associated with the development of suicidal behavior. A 1.7- to 10.6-fold risk of developing suicidal behavior has been observed in individuals with first- or second-degree relatives with suicidal behavior. It has been suggested that the serotonergic and dopaminergic systems are involved in suicide attempts, particularly the SLC6A4 and MAOA genes.

Objective: To analyze the allele transmission of 5-HTTLPR/SLC6A4 and uVNTR/MAOA polymorphisms in families with suicide attempts.

Method: Fifty families with proband with a history of suicide attempts were included. All participants were recruited at the Ramón de la Fuente Muniz National Institute of Psychiatry and evaluated using the International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.). Allele transmission analysis of the 5-HTTLPR and uVNTR polymorphisms was performed using the Haploview program.

Results: Analysis of allele transmission of the 5-HTTLPR/SLC6A4 polymorphism showed greater transmission of the S allele in probands (χ2 = 6.6, p = .0098) with a previous suicide attempt and in those with two or more suicide attempts (χ2 = 5.4, p = .019). There was no observed preference in uVNTR/MAOA allele transmission.

Discussion and conclusion: Our data support the hypothesis that the serotonin transporter is implicated in the development of suicide attempts in Mexican patients with mood disorders.

Keywords: Suicide attempt, 5-HTTLPR/SLC6A4, uVNTR/MAOA..

Resumen:

Introducción: Los factores biológicos, principalmente los genéticos, se encuentran vinculados al desarrollo de la conducta suicida. Se ha observado un incremento de 1.7 a 10.6 veces el riesgo a desarrollar conducta suicida en individuos con antecedentes de familiares de primer o segundo grado con conducta suicida. Se sugiere que el sistemas serotoninérgico y dopaminérgico se encuentran implicados con el intento suicida, destacando los genes SLC6A4 y MAOA.

Objetivo: Analizar la transmisión de los alelos de los polimorfismos 5-HTTLPR/SLC6A4 y uVNTR/MAOA en familias con intento suicida.

Método: Se incluyeron cincuenta familias donde el probando tenía el antecedente de intento suicida. Todos los participantes fueron obtenidos en el Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz evaluados con la Entrevista Neuropsiquiátrica Internacional (M.I.N.I.). El análisis de transmisión de alelos de los polimorfismos 5-HTTLPR y uVNTR se realizó mediante el uso del programa Haploview.

Resultados: El análisis del polimorfismo 5-HTTLPR/SLC6A4 mostró una mayor transmisión del alelo S en los probandos con un intento suicida previo (χ2 = 6.6, p = .0098) y en aquellos con dos o más intentos suicidas (χ2 = 5.4, p = .019). No se observó la transmisión preferente de algún alelo del polimorfismo uVNTR/MAOA en la muestra analizada.

Discusión y conclusión: Nuestros datos respaldan la hipotesis de que el transportador de serotonina se encuentra implicado con el desarrollo del intento suicida en pacientes mexicanos con trastornos del ánimo.

Palabras clave: Intento suicida, 5-HTTLPR/SLC6A4, uVNTR/MAOA..

INTRODUCTION

Suicide is a worldwide public health problem affecting all ages and genders, as noted by the WHO (Bachmann, 2018). It claims approximately 1.53 million lives annually, with attempts being ten to twenty times more prevalent. This is equivalent to an average mortality rate of one person every twenty seconds and an attempt every one to two seconds, reflecting its impact on global health (Bertolote & Fleishman, 2002). The incidence of suicide displays regional variations, reflecting differing mortality rates among continents. Mexico’s annual suicide rate stands at five per 100,000 inhabitants, making it one of the countries with the lowest rates (Borges et al., 2010). Campillo & Dolci (2021) reported that suicide mortality rose by 175% between 1970 and 2007, culminating in 4,388 cases in 2007, with a rate of 4.12 per 100,000 individuals. This sharp rise warrants a closer look at the causes behind this concerning trend.

The association between suicide and psychiatric disorders is well-documented, with affective disorders, substance use, psychosis, eating disorders, and certain personality disorders being common contributors (Brådvik, 2018). Mood disorders, particularly depression, have been identified as the most frequent psychiatric conditions linked to completed suicides (Isometsä, 2014; Rihmer & Rihmer, 2019). Although psychopathology predicts suicide risk, most diagnosed individuals do not attempt suicide.

Twin and adoption studies have highlighted the genetic components involved in suicide. Other studies show that suicidal behavior is transmitted within families (Brent & Melhem, 2008; Turecki & Brent, 2016), underlining the need to consider genetics in suicide prevention strategies. Studies have examined the link between key enzyme genes, serotonin transporters, and suicidal behavior. The serotonin transporter gene SLC6A4 has been strongly associated with suicide attempts (Gonda et al., 2011). The SLC6A4 gene located on chromosome 17 (17q11.1-12), and a polymorphism in the promoter region, known as 5-HTTLPR, characterized by an insertion/deletion of a 44 base pair fragment, have been linked to suicidal behavior. This polymorphism has two alleles: the short form “S” (deletion) and the long variant “L” (insertion). The “SS” genotype and the “S” allele of the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism have been positively linked to completed suicides, suicide attempts, and a family history of suicidal behavior (Li & He, 2007). Nevertheless, there have been inconsistent findings across studies regarding these results (Turecki, 2014; Picouto & Braquehais, 2015). Another gene of interest encodes monoamine oxidase type A (MAOA), a crucial enzyme for neurotransmitter metabolism, including serotonin. Located on the short arm of chromosome Xp11.3, the MAOA gene also contains a variable number tandem repeat (uVNTR) polymorphism in the promoter region. It comprises thirty base pairs and expresses alleles with two, three, four, and five copies, each conferring different levels of transcriptional activity (Sabol et al., 1998).

Research in Mexico has established a genetic link to suicidal behavior, as demonstrated by the studies by Genis-Mendoza et al. (2017), González-Castro et al. (2019), Sarmiento-Hernández et al. (2019), Cabrera-Mendoza et al. (2020), and Sanabrais-Jiménez et al. (2022). Despite this progress, there is a dearth of family-based studies in this context. This study seeks to fill that gap by analyzing the transmission of alleles for the 5-HTTLPR/SCL6A4 and uVNTR/MAOA polymorphisms in families where the proband has both a history of suicide attempts and a primary mood disorder diagnosis. We also aimed to compare demographic and clinical features between probands and their first-degree relatives.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were recruited through the outpatient, emergency, and hospitalization services at the INPRFM in Mexico City. Participants included adults over 18 with a lifetime history of suicide attempts, a primary mood disorder diagnosis according to DSM IV-TR (Segal, 2010), and at least one biological parent available during the study period. All participants completed the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.) to confirm primary diagnoses and identify psychiatric comorbidities (Sheehan et al., 1998).

Assessment procedures

Demographic and clinical features were registered in an ad hoc sheet report. These included sex, age, current diagnosis (major depressive disorder, dysthymia, bipolar disorder), and age of illness onset. Other characteristics included current use of substances (nicotine, alcohol, marijuana, cocaine) and suicide attempt features (number of suicide attempts and method used in the last suicide attempt).

For genetic analysis, family-based association test (FBAT) methodology requires the genotyping of parents and probands to conduct the transmission analysis of variants. We therefore obtained a 5 ml sample of peripheral blood from the father, mother and proband for family trios and from the parent and proband for dyads.

Genetic analysis

Genomic DNA from all participants (parents and probands) was isolated from peripheral blood lymphocytes using a high-salt method. The endpoint PCR analysis of the 5-HTTLPR/SLC6A4 polymorphism was performed in a total volume of 15 µl, containing 1.8 mM of MgCl2, 200 mM each of dATP, dCTP, and dTTP, 100 mM each of dGTP and 7-deaza-dGTP, 0.96 units of AmpliTaq Gold polymerase (AmpliTaq Gold [Product], Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, CT, USA), 1.3 μl of primers (5-GGC GTT GCC GCT CTG AAT TGC and 5-GAG GGA CTG AGC TGG ACA ACC CAC) and 150 ng of genomic DNA. The amplification conditions consisted of an initial denaturation step of ten minutes at 95°C; forty-five cycles consisting of thirty seconds at 95°C, thirty seconds at 61°C, and one minute at 72°C, followed by a final step of seven minutes at 72°C. PCR products were separated on 2% high-melting-point agarose gels and visualized under UV after ethidium bromide staining (Camarena et al., 2001). Analysis of the uVNTR/MAOA polymorphism was performed in keeping with the conditions described by Sabol et al. (1998). The amplification product was run on 3% MetaPhor gels and visualized under UV light after staining with ethidium bromide.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were described using frequencies and percentages, while means and standard deviations were used to summarize continuous variables.

Chi-Square (χ2) tests and Student’s t-tests were used to compare patients with a history of suicide attempts with their parents. The level of significance was set at p < .05. All analyses were performed using the R Studio statistical program version 1.0.136 (R Core Team, 2018).

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium analysis was conducted with the HWE software (available at https://wpcalc.com/en/equilibrium-hardy-weinberg/). Allele transmission of the 5-HTTLPR/SLC6A4 and uVNTR/MAOA polymorphisms was analyzed with the set of family-based association tests using the Haploview program, version 4.1 (Barrett et al. 2005).

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Ethics and Research Committees of the Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz National Institute of Psychiatry (INPRFM). All participants gave voluntary, informed consent after the study’s objectives and procedures had been explained. None of the participants received any form of compensation for their participation in the study. Family members diagnosed with psychiatric conditions during the interview were informed of their diagnosis and recommended to arrange a clinical consultation at the outpatient services of the INPRFM for further evaluation and treatment.

RESULTS

Demographic and clinical characteristics

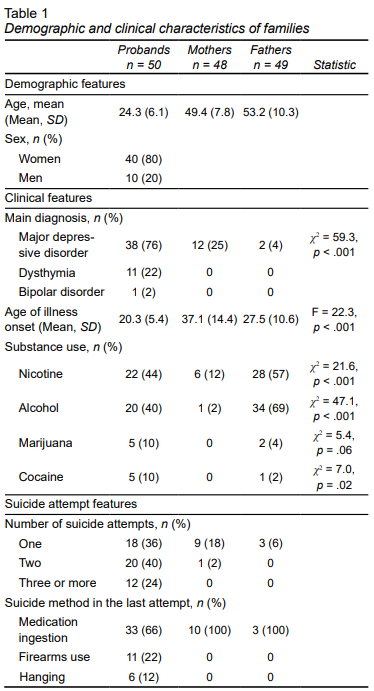

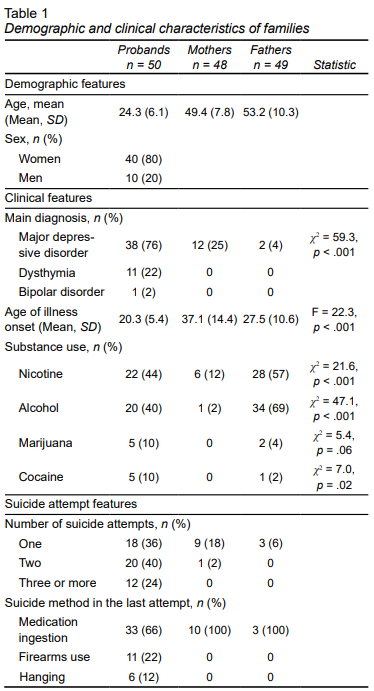

A total of fifty families were included, 94% of which (n = 47) were trios (proband, mother, and father), while the remaining 6% were dyads consisting of the patient and one parent. The average number of suicide attempts among probands was two (SD = 1). The demographic and clinical characteristics of probands, mothers, and fathers are given in Table 1. A higher number of probands had a diagnosis of major depressive disorder than the group of parents. (Table 1). In addition, mothers had a lower frequency of comorbidity with the use of nicotine, alcohol, and cocaine than probands and fathers.

view

Allele transmission analysis

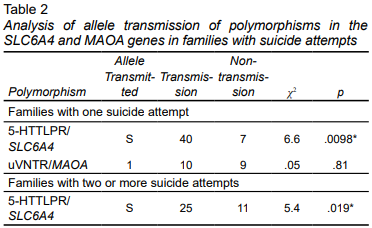

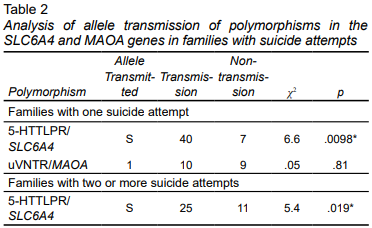

Genotype distribution conformed to Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p > .05). Table 2 showed the allele transmission analyses for the 5-HTTLPR/SLC6A4 and uVNTR/MAOA polymorphisms in the fifty families studied. For the 5-HTTLPR/SLC6A4 polymorphism, there was a preferential transmission of the S allele in the general sample (χ2 = 6.6, p = .0098). In the allele transmission analysis of the MAOA gene, no preferential allele transmission was observed (χ2 = .053, p = .8185).

view

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants are consistent with those reported in previous research. Suicide attempts have been found to occur more frequently among women than men (Bachmann, 2018), predominantly affecting individuals aged between 15 and 29 (Aguilar-Velázquez et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2020). In terms of clinical characteristics, research has consistently shown that mood disorders increase suicide risk, identifying them as a critical risk factor within the realm of psychopathology (Jamison, 2000; Tondo et al., 2020). The inclusion criteria for this study were therefore designed to encompass patients diagnosed with a mood disorder with a lifetime history of suicide attempts.

Disorders related to the use of alcohol and other substances have been identified as significant risk factors not only for suicidal behavior, but also for the presence of psychopathology (Lee et al., 2019; Lynch et al., 2020). Our study was no exception, as most of the population studied reported substance use, with nicotine and alcohol use being more frequent. No differences were found in suicidal methods compared to other studies analyzing this variable. More violent and lethal methods such as hanging are used in completed suicides, while non-violent methods such as drug ingestion are usually the method of choice in suicide attempts (Kposowa & McElvain, 2006; Tsirigotis, et al, 2011).

Regarding the allele transmission analysis of the uVNTR polymorphism of the MAOA gene in families with suicide attempts, no transmission of any alleles was observed in the complete sample. Our study is therefore consistent with the only other report analyzing the association between the MAOA gene and suicide attempts in families (De Luca et al., 2005).

In addition, our study showed a higher transmission of the S allele in families with suicide attempts, as well as in those with two or more suicide attempts. Zalsman et al. (2001) conducted a family-based association study of 5-HTTLPR/SLC6A4 without finding significant differences. It is important to note that both studies were conducted in families where all probands presented at least one suicide attempt. However, our study only analyzed probands with a primary diagnosis of a mood disorder, while the other study included patients with other psychiatric disorders. Our data suggest that the transmission of the S allele could be specifically implicated in patients with suicide attempts and a primary diagnosis of a mood disorder.

Although gamily-based association studies constitute a significant method for exploring the genetic foundations of complex behaviors like suicide, they are not the only approach for examining the links between candidate genes and familial suicide history. Joiner et al. (2002) focused on the 5-HTTLPR/SLC6A4 polymorphism in forty-seven volunteers, assessing their family history of suicidal behavior. Their findings indicated that carriers of the SS genotype reported a greater incidence of suicide completion and multiple suicide attempts among first-degree relatives than carriers of SL and LL genotypes. Our findings therefore align with and support previous family studies in the literature, suggesting the involvement of the S allele of the 5-HTTLPR/SLC6A4 polymorphism in the genetic etiology of suicide attempts.

Some studies have reported an association between the S allele of the 5-TTLPR/SLC6A4 polymorphism, and the presence of violent suicide attempts in patients with affective disorders (Fanelli & Serretti, 2019; Sivaramakrishnan et al, 2023). In addition, it has been observed that carriers of the S allele presented two or three times less expression of the SLC6A4 gene than carriers of the L allele (Lesch et al., 1996). Moreover, some studies have shown that being a carrier of the low-expression allele of 5-HTTLPR/SLC6A4 is associated with elevated levels of aggression and impulsivity (Waltes, et al, 2016). Our findings could suggest that higher transmission of the S allele of the 5-HTTLPR in SLC6A4 gene, which implies lower expression of the gene, could be associated with aggression and impulsivity, acting as triggers for the suicide attempt.

Limitations

Our study has certain limitations. The first was the small sample size, which restricts the generalizability of our results. The latter should therefore be interpreted with caution, and regarded as preliminary until they are replicated in a larger sample. The second is that only the SLC6A4 and MAOA genes were analyzed. Suicidal behavior is a complex phenomenon involving multiple genes across neurobiological systems, including polyamines, GABAergic, neuroinflammatory pathways, lipid metabolism, and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (Lutz et al., 2017).

There is a higher observed prevalence of “S” allele transmission within families with a documented history of suicide attempts. This reinforces the theory that the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene plays a significant role in the manifestation of suicidal behaviors among individuals with mood disorders, as well as their immediate family members. This finding underscores the genetic underpinnings of suicidal tendencies, highlighting the importance of considering familial genetic patterns when assessing suicide risk, to provide a more nuanced understanding of its etiology in the context of mood disorders.

Funding

None.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

None.

REFERENCES

Aguilar-Velázquez, D. G., González-Castro, T. B., Tovilla-Zárate, C. A., Juárez-Rojop, I. E., López-Narváez, M. L., Fresán, A., Hernández-Díaz, Y., & Guzmán-Priego, C. G. (2017). Gender differences of suicides in children and adolescents: Analysis of 167 suicides in a Mexican population from 2003 to 2013. Psychiatry Research, 258, 83-87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.09.083

Bachmann, S. (2018). Epidemiology of Suicide and the Psychiatric Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(7), 1425. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15071425

Barrett, J. C., Fry, B., Maller, J., & Daly, M. J. (2005). Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics, 21(2), 263-265. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457

Bertolote, J. M., & Fleischmann, A. (2002). Suicide and psychiatric diagnosis: a worldwide perspective. World Psychiatry, 1(3), 181-185. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1489848/

Borges, G., Orozco, R., Benjet, C., & Medina-Mora, M. E. (2010). Suicide and suicidal behaviors in Mexico: Retrospective and current status. Salud Publica de México, 52(4), 292-304. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20657958/

Brådvik, L. (2018). Suicide Risk and Mental Disorders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(9), 2028. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15092028

Brent, D. A., & Melhem, N. (2008). Familial Transmission of Suicidal Behavior. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 31(2), 157-177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2008.02.001

Cabrera-Mendoza, B., Martínez-Magaña, J. J., Genis-Mendoza, A. D., Sarmiento, E., Ruíz-Ramos, D., Tovilla-Zárate, C. A., González-Castro, T. B., Juárez-Rojop, I. E., García-de la Cruz, D. D., López-Armenta, M., Real, F., García-Dolores, F., Flores, G., Vázquez-Roque, R. A., Lanzagorta, N., Escamilla, M., Saucedo‐Uribe, E., Rodríguez-Mayoral, O., Jiménez-Genchi, J., Castañeda-González, C., Roche-Bergua, A., & Nicolini, H. (2020). High polygenic burden is associated with blood DNA methylation changes in individuals with suicidal behavior. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 123, 62-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.01.008

Camarena, B., Rinetti, G., Cruz, C., Hernández, S., de la Fuente, J. R., & Nicolini, H. (2001). Association study of the serotonin transporter gene polymorphism in obsessive-compulsive disorder. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 4(3), 269-272. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11602033/

Campillo Serrano, C., & Fajardo-Dolci, G. (2021). Suicide prevention and suicidal behavior. Gaceta Médica de México, 157(5). https://doi.org/10.24875/gmm.m21000611

De Luca, V., Tharmalingam, S., Sicard, T., & Kennedy, J. L. (2005). Gene-gene interaction between MAOA and COMT in suicidal behavior. Neuroscience Letters, 383(1-2), 151-154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2005.04.001

Fanelli, G., & Serretti, A. (2019). The influence of the serotonin transporter gene 5-HTTLPR polymorphism on suicidal behaviors: a meta-analysis. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 88, 375-387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2018.08.007

Genis-Mendoza, A., López-Narvaez, M., Tovilla-Zárate, C., Sarmiento, E., Chavez, A., Martinez-Magaña, J., González-Castro, T., Hernández-Díaz, Y., Juárez-Rojop, I., Ávila-Fernández, Á., & Nicolini, H. (2017). Association between Polymorphisms of the DRD2 and ANKK1 Genes and Suicide Attempt: A Preliminary Case-Control Study in a Mexican Population. Neuropsychobiology, 76(4), 193-198. https://doi.org/10.1159/000490071

Gonda, X., Fountoulakis, K. N., Harro, J., Pompili, M., Akiskal, H. S., Bagdy, G., & Rihmer, Z. (2011). The possible contributory role of the S allele of 5-HTTLPR in the emergence of suicidality. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 25(7), 857-866. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881110376693

González‐Castro, T. B., Martínez‐Magaña, J. J., Tovilla‐Zárate, C. A., Juárez‐Rojop, I. E., Sarmiento, E., Genis‐Mendoza, A. D., & Nicolini, H. (2019). Gene‐level genome‐wide association analysis of suicide attempt, a preliminary study in a psychiatric Mexican population. Molecular Genetics & Genomic Medicine, 7(12). https://doi.org/10.1002/mgg3.983

Isometsä, E. (2014). Suicidal Behaviour in Mood Disorders—Who, When, and Why? The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 59(3), 120-130. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371405900303

Jamison, K. R. (2000). Suicide and bipolar disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 61(Suppl 9), 47-51. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10826661/

Joiner, T. E., Johnson, F., & Soderstrom, K. (2002). Association Between Serotonin Transporter Gene Polymorphism and Family History of Attempted and Completed Suicide. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 32(3), 329-332. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.32.3.329.22167

Kposowa, A. J., & McElvain, J. P. (2006). Gender, place, and method of suicide. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 41(6), 435-443. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-006-0054-2

Lee, J., Min, S., Ahn, J., Kim, H., Cha, Y., Oh, E., Moon, J. S., & Kim, M. (2019). Identifying alcohol problems among suicide attempters visiting the emergency department. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2347-5

Lesch, K., Bengel, D., Heils, A., Sabol, S. Z., Greenberg, B. D., Petri, S., Benjamin, J., Müller, C. R., Hamer, D. H., & Murphy, D. L. (1996). Association of Anxiety-Related Traits with a Polymorphism in the Serotonin Transporter Gene Regulatory Region. Science, 274(5292), 1527-1531. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.274.5292.1527

Li, D., & He, L. (2007). Meta-analysis supports association between serotonin transporter (5-HTT) and suicidal behavior. Molecular Psychiatry, 12(1), 47-54. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.mp.4001890

Lutz, P., Mechawar, N., & Turecki, G. (2017). Neuropathology of suicide: recent findings and future directions. Molecular Psychiatry, 22(10), 1395-1412. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2017.141

Lynch, F. L., Peterson, E. L., Lu, C. Y., Hu, Y., Rossom, R. C., Waitzfelder, B. E., Owen-Smith, A. A., Hubley, S., Prabhakar, D., Keoki Williams, L., Beck, A., Simon, G. E., & Ahmedani, B. K. (2020). Substance use disorders and risk of suicide in a general US population: a case control study. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-020-0181-1

Picouto, M. D., Villar, F., & Braquehais, M. D. (2015). The role of serotonin in adolescent suicide: theoretical, methodological, and clinical concerns. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 27(2), 129-133. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2015-5003

R Core Team. (2018). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/

Rihmer, Z., & Rihmer, A. (2019). Depression and suicide - the role of underlying bipolarity. Psychiatria Hungarica, 34(4), 359-368. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31767796/

Sabol, S. Z., Hu, S., & Hamer, D. (1998). A functional polymorphism in the monoamine oxidase A gene promoter. Human Genetics, 103(3), 273-279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004390050816

Sanabrais-Jiménez, M. A., Aguilar-García, A., Hernández-Muñoz, S., Sarmiento, E., Ulloa, R. E., Jiménez-Anguiano, A., & Camarena, B. (2022). Association study of Catechol-O-Methyltransferase (COMT) rs4680 Val158Met gene polymorphism and suicide attempt in Mexican adolescents with major depressive disorder. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 76(3), 202-206. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039488.2021.1945682

Sarmiento-Hernández, E. I., Ulloa-Flores, R. E., Camarena-Medellín, B., Sanabrias-Jiménez, M. A., Aguilar-García, A., & Hernández-Muñoz, S. (2019). Association between 5-HTTLPR polymorphism, suicide attempt, and comorbidity in Mexican adolescents with major depressive disorder. Actas Españolas de Psiquiatría, 47(1), 1-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30724325/

Segal, D. L. (2010). Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (DIS-IV). The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470479216.corpsy0273

Sheehan, D. V., Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, K. H., Amorim, P., Janavs, J., Weiller, E., Hergueta, T., Baker, R., & Dunbar, G. C. (1998). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59(Suppl 20), 22-33. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9881538/

Sivaramakrishnan, S., Venkatesan, V., Paranthaman, S. K., Sathianathan, R., Raghavan, S., & Pradhan, P. (2023). Impact of Serotonin Pathway Gene Polymorphisms and Serotonin Levels in Suicidal Behaviour. Medical Principles and Practice, 32(4-5), 250-259. https://doi.org/10.1159/000534069

Tondo, L., Vazquez, G. H., & Baldessarini, R. J. (2020). Suicidal Behavior Associated with Mixed Features in Major Mood Disorders. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 43(1), 83-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2019.10.008

Tsirigotis, K., Gruszczynski, W., & Tsirigotis-Woloszczak, M. (2011). Gender differentiation in methods of suicide attempts. Medical Science Monitor, 17(8), PH65-PH70. https://doi.org/10.12659/msm.881887

Turecki, G. (2014). The molecular bases of the suicidal brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 15(12), 802-816. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3839

Turecki, G., & Brent, D. A. (2016). Suicide and suicidal behaviour. The Lancet, 387(10024), 1227-1239. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(15)00234-2

Waltes, R., Chiocchetti, A. G., & Freitag, C. M. (2016). The neurobiological basis of human aggression: A review on genetic and epigenetic mechanisms. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics, 171(5), 650-675.

Wu, Y., Schwebel, D. C., Huang, Y., Ning, P., Cheng, P., & Hu, G. (2020). Sex-specific and age-specific suicide mortality by method in 58 countries between 2000 and 2015. Injury Prevention, 27(1), 61-70. https://doi.org/10.1136/injuryprev-2019-043601

Zalsman, G., Frisch, A., Bromberg, M., Gelernter, J., Michaelovsky, E., Campino, A., Erlich, Z., Tyano, S., Apter, A., & Weizman, A. (2001). Family‐based association study of serotonin transporter promoter in suicidal adolescents: No association with suicidality but possible role in violence traits. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 105(3), 239-245. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.1261