INTRODUCTION

Schizophrenia is a chronic, complex, multifactorial psychiatric disorder with clinical manifestations that include positive symptoms such as delusions, hallucinations, disorganized thinking and disorganized behavior, and negative symptoms such as anhedonia, social withdrawal, flat affect, alogia, and apathy (Millier et al., 2014). This condition also encompasses neurocognitive failures associated with occupational and social outcomes. (Mihaljević-Peleš et al., 2019). Schizophrenia has a lifetime prevalence of 1% and an incidence of 15 cases per 100,000 population, with onset usually occurring in early adolescence (Hasan et al., 2020). The ratio of women to men with schizophrenia is 1:1.3 (Sommer et al., 2020).

Antipsychotic drugs are the mainstay of treatment for schizophrenia, their mechanism of action being to regulate dopaminergic neurotransmission. Most first-generation antipsychotics work by blocking dopamine D2 receptors to varying degrees. Second-generation or atypical antipsychotic drugs employ additional mechanisms to regulate dopaminergic function, such as partial antagonism of dopamine receptors and antagonism. They also use partial antagonism of serotonin receptors to improve psychotic symptoms while reducing the incidence of extrapyramidal symptoms (McCutcheon et al., 2020; Owen et al., 2016). Among second-generation antipsychotic drugs, partial agonists–aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, and cariprazine–constitute a subclass, as their mechanism of action involves the partial agonism of D2 receptors. Partial agonism regulates dopamine tone, which has been hypothesized to reduce the incidence of adverse effects and the risk of dopamine supersensitivity psychosis (Frankel & Schwartz, 2017).

Aripiprazole, the first partial agonist, was first released in 2002. It decreases D2 transmission without full receptor blockade. In the absence of dopamine, it increases D2-mediated transmission (Kikuchi et al., 2021). The receptor-binding affinities (Ki, nmol/L) of aripiprazole are D2 = .34, D3 = .8, serotonin 5-HT1A = 1.7, 5-HT2A = 3.4, 5-HT2C = 96, 5-HT7 = 39, alpha1 = 52, histamine H1 = 61, and muscarinic acetylcholine M₁ = 6800 (Kikuchi et al., 2021).

Brexpiprazole, first introduced in 2015, was designed to improve tolerability, mainly by reducing the risk of side effects reported with aripiprazole: akathisia, restlessness, and sleep disturbances (Kikuchi et al., 2021). The receptor-binding affinities (Ki, nmol/L) of brexpiprazole are D2 = .30, D3 = 1.1, 5-HT1A = .12, 5-HT2A = .47, 5-HT2C = 34, 5-HT7 = 3.7, alpha1 = 3.8, H1 = 19, and M1 ≥ 1000 (Kikuchi et al., 2021).

Important differences exist between brexpiprazole and aripiprazole treatments. The clinical profile of brexpiprazole shows lower intrinsic activity on the dopamine agonist spectrum than aripiprazole, which has fewer effects such as activation, agitation, and akathisia, enabling better overall tolerability (Stahl, 2016).

Brexpiprazole has a similar effect to aripiprazole in reducing psychotic symptoms and similar rates of metabolic adverse effects (Ward & Citrome, 2019). Both drugs are associated with a reduced incidence of all-cause discontinuation compared to placebo (Kishi et al., 2020). Aripiprazole acts through 5HT2A antagonism, 5HT1A agonism, and alpha 1B antagonism to mitigate extrapyramidal side effects, but brexpiprazole has greater potency at each of the three receptors (Stahl, 2016). The higher affinity for 5-HT1A could reflect the greater effectiveness of brexpiprazole in the treatment of depressive symptoms (Citrome et al., 2016a). Moreover, the lower antihistaminergic properties of brexpiprazole may reduce somnolence and sedation (Stahl, 2016). Compared to aripiprazole, brexpiprazole has fewer sedative and activating adverse effects (Ward & Citrome, 2019) and may demonstrate greater efficacy in improving positive and cognitive symptoms (Citrome et al., 2016a). A pooled analysis of schizophrenia trials reported a number needed to treat (NNT) of eight for aripiprazole vs. placebo, and an NNT of seven for brexpiprazole vs. placebo. Response was defined as a 30% or more decrease in the total Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) score or a Clinical Global Impression-Improvement (CGI-I) score of 1 or 2 (very much improved or much improved;Citrome, 2015). Although antipsychotic medication can help reduce positive symptoms, the negative syndrome is more difficult to treat, with mixed results in clinical trials (Correll & Schooler, 2020).

Despite the literature highlighting the benefits of brexpiprazole compared to aripiprazole, studies such asHuhn et al., (2019) found that treatment with aripiprazole resulted in more effective symptom reduction (general, positive, negative and depressive symptoms) and better tolerability (all-cause discontinuation risk ratio (RR) .80, 95% confidence interval (CI) .73 to .86) compared with brexpiprazole (RR .89, 95% CI .80 to .98). Other outcomes included akathisia, where brexpiprazole ranked slightly better than aripiprazole (RR 1.35 with brexpiprazole vs RR 1.95 with aripiprazole), and prolactin elevation, where aripiprazole ranked better than brexpiprazole. These data indicate that the superiority of brexpiprazole over other molecules is not confirmed (Huhn et al., 2019).

Aripiprazole has proven useful in the treatment of psychotic symptoms, as well as in the treatment of adverse effects and comorbidities. Some research has indicated that brexpiprazole may have greater efficacy than aripiprazole and a similar or better tolerability profile. It is therefore important to examine the available evidence to compare these two medications, as both are widely accessible yet have varying costs.

There are multiple protocols but only seven Cochrane Reviews of aripiprazole in people with schizophrenia (Belgamwar & El‐Sayeh, 2011; Bhattacharjee & El‐Sayeh, 2008; Brown et al., 2013; El-Sayeh & Morganti, 2006; Hirsch & Pringsheim, 2016; Khanna et al., 2014; Ostinelli et al., 2018) and no reviews for brexpiprazole, only two protocols (Bazrafshan et al., 2017; Ralovska et al., 2023).

Some studies have compared the efficacy, safety and tolerability of aripiprazole versus brexpiprazole in individuals with fewer than four weeks of treatment (Kishi et al., 2020). Our review will focus on medium- (six weeks to six months) and long-term treatment (over six months) and will obtain additional information on outcomes such as quality of life, behavior, cognitive functioning, and service use. To our knowledge, no other meta-analyses have included these measures, which is why this review could contribute to increasing information on the effects of aripiprazole versus brexpiprazole. The present review aimed to assess the efficacy and tolerability of aripiprazole compared to brexpiprazole in people diagnosed with schizophrenia or schizophrenia-like psychosis.

METHOD

Eligibility criteria

Studies: We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in the search, as well as studies reported as full-text articles.

Participants: Adults (over 18 years of age) of both sexes with diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia or related disorders, including schizoaffective disorder. Since we were interested in the phases of the illness that could be treated with antipsychotic drugs, we excluded the prodromal phase and included people with first-episode schizophrenia, and early and persistent illness in the search.

To ensure that the results were as relevant as possible to the current care of people with schizophrenia, studies focusing on those with specific problems (such as negative symptoms, adverse reactions, or treatment-resistant illness) were included in the search.

Interventions:1) Aripiprazole is available in oral and long-acting injectable (LAI) depot formulations. The dose range of the oral formulation was between 10 mg/day and 30 mg/day. The doses considered for therapeutic use were up to 400 mg/month for the LAI (long-acting injectable) formulation. 2) Brexpiprazole is accessible as an oral formulation. For this review, doses ranging from 2 mg/day to 4 mg/day (the established therapeutic doses) were contemplated.

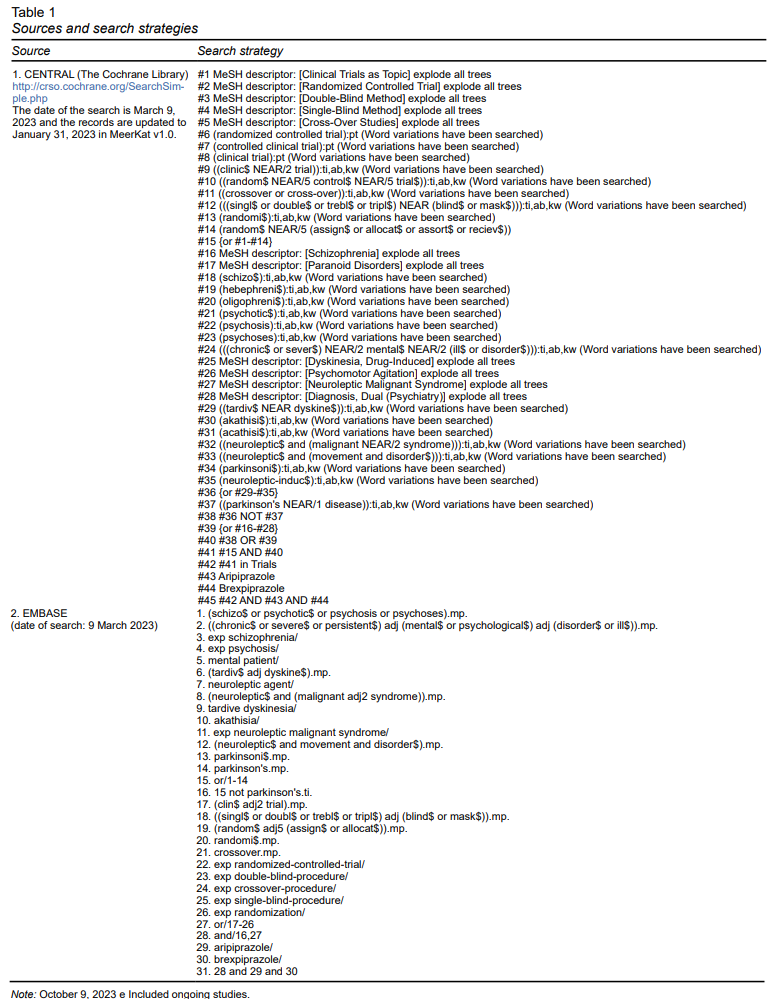

Search methods for identifying studies

The search was conducted by the Cochrane schizophrenia group information specialist on March 9, 2023. The MEERKAT registry was searched in March 2023 using (*Aripiprazole* AND *Brexpiprazole*). Since few references were retrieved in this system, a search was performed in the EMBASE and Cochrane CENTRAL trial databases.

The Information Specialist compiled this register from systematic searches of the following major resources: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and Embase. As explained on the Schizophrenia Group website (schizophrenia.cochrane.org/register-trials), the register also included hand searching and conference proceedings. It did not place any limitations on language, date, document type, or publication status. The search strategies used can be seen in Table 1. The reference lists of all included studies were checked for other relevant studies. We attempted to contact the first author of the relevant unpublished studies, but received no response, so we did not include them in this review. (For the complete protocol of this systematic review seeMartínez-Vélez et al., 2023).

Procedure

The search records were imported into the Covidence software (www.covidence.org). During the first stage of screening, two of the authors (YF and MR) independently screened study titles and abstracts to rule out those that were clearly ineligible and another author (RS) acted as referee. Two other reviewers (YF and AG) independently obtained and reviewed full reports of all potentially eligible records. Where disagreements could not be resolved by discussion, the lead author of the review team (NM) was consulted.

Two researchers (YF, AG) performed data extraction using the Covidence extraction template. Extraction was performed independently, considering the relevant results of the included study.

The following variables were extracted: Study identification (source of sponsorship, country, setting, author(s)’ name(s), institution(s), email(s), and address(es)), Methods (study design and group), and Population (inclusion and exclusion criteria). For outcomes, we utilized the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), Clinical Global Impression-Severity (CGI-S), and Composite Cognitive Test Battery reported as least square at Week 6 of treatment. We also used the Simpson-Angus Extrapyramidal Side Effects Scales, Clinical Global Impression-Improvement (CGI-I), Abnormal Involuntary Movements Scale, Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale (BARS), Change in Body Weight, and Body Mass Index. We collected mean and standard deviation changes from baseline at Week 6 for cholesterol, HDL, LDL, triglycerides, glucose, and prolactin.

Forms: Covidence (www.covidence.org) was used, and data were entered and subsequently exported to the Review Manager Web (RevMan Web 2023). RevMan Web.

Assessment of Risk of Bias in Included Studies: Two reviewers (YF, AG) independently assessed the risk of bias in the included trial using the criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions presented in Appendix 3 (Higgins et al., 2023). This is based on evidence of associations between possible overestimation of effect and level of risk of bias or as reported by domains. For this review, this included sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other sources of bias. When evaluators disagreed, the final rating was considered by consensus, with all decisions being documented.

Assumptions about participants who dropped out or were lost to follow-up. The included study did not analyze participants who completed the study. For assumptions about participants who dropped out or were lost to follow-up, the last observation carried forward (LOCF) method was chosen for the only study included in this review.

Since there was only one study, it was not possible to conduct a graphic or statistical evaluation of reporting biases.

We used the GRADE approach to assess the certainty of the evidence (Schünemann et al., 2023); and theGRADEpro GDT (2015) to export data from our review and create one summary of findings table. This table provided outcome- specific information concerning the overall certainty of evidence from the study included the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on all outcomes we rated as important for patient care and decision-making.

RESULTS

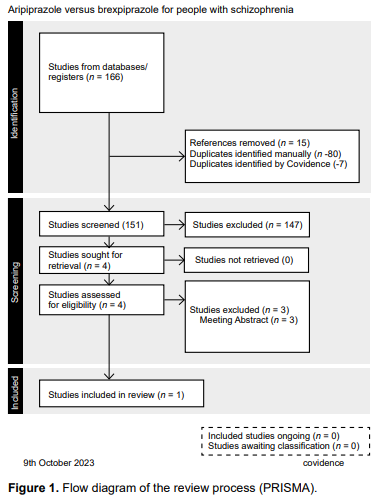

A single study with the established features was identified. The main analysis therefore concerned the only study included after all the steps described in the flow diagram (PRISMA) (Figure 1). We found 166 records from electronic searches, fifteen of which were eliminated because they were duplicated, meaning that the titles and abstracts of 151 records were examined. Of these, only four full texts were retrieved, and their eligibility was assessed according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria described in the protocol (type of study, population and intervention). During this process, three studies were excluded, and finally, only one study met the criteria for inclusion in this review.

Included studies

The characteristics of the included study are presented (Citrome et al., 2016a)

Design: This was an exploratory, open-label, multicenter, flexible-dose study of adult patients conducted between February 27, 2014 and July 25, 2014 at nineteen sites across the United States. Patients were randomly assigned 2:1 to receive brexpiprazole or aripiprazole.

Participants: A total of ninety-seven patients were randomized, with sixty-four patients receiving brexpiprazole and thirty-three receiving aripiprazole. A total of sixty-one (62.9%) patients completed the study, forty (62.5%) in the brexpiprazole group and twenty-one (63.6%) in the aripiprazole group.

Inclusion criteria: Adult patients aged 18–65 with a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed., text revision (DSM-IV-TR) diagnosis of schizophrenia confirmed by the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Schizophrenia and Psychotic Disorders.

Exclusion criteria: Patients were excluded if they were presenting with a first episode of schizophrenia, or had been hospitalized for more than twenty-one days for the current acute episode. They were also excluded if they had a current DSM-IV-TR Axis 1 diagnosis other than schizophrenia, or showed an improvement of 20% or more in the total PANSS score between screening and baseline assessments.

Interventions

Brexpiprazole: Treatment for six weeks up to 4 mg/day, once daily dose, tablets, oral or brexpiprazole for six weeks up to 20 mg/day, once daily dose, tablets, orally, Brexpiprazole (1–4 mg/ day) starting at 1 mg/day and titrating to a target dosage of 3 mg/day at the end of week 1 for brexpiprazole. Dosage adjustments occurred in stepwise increments or decrements of 1 mg for brexpiprazole. Dosage increases were only allowed at scheduled visits, whereas decreases could have occurred at any time during the trial following the Week 1 visit. Adjustments were made according to the clinical judgment of the investigator.

Aripiprazole: Treatment for six weeks up to 4 mg/day, once daily dose, tablets, oral or Aripiprazole for six weeks up to 20 mg/day, once daily dose, tablets, orally. Aripiprazole (10–20 mg/day), starting at 10 mg/day and titrating to a target dosage of 15 mg/day at the end of week 1 for aripiprazole. Dosage adjustments occurred in stepwise increments or decrements of 5 mg for aripiprazole. Dosage increases were only allowed at scheduled visits, whereas decreases could have occurred at any time during the trial following the Week 1 visit. Adjustments were made based on the clinical judgment of the investigator.

Outcomes: Included change from baseline to Week 6 in the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total score, Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11 score, and Cogstate computerized cognitive test battery scores. Patients treated with brexpiprazole (n = 64) or aripiprazole (n = 33) showed reductions in symptoms of schizophrenia as assessed by the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total score (−22.9 and −19.4, respectively). A modest reduction in impulsivity was observed with brexpiprazole, but not aripiprazole (mean change in the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11 total score: − 2.7 and .1, respectively). No change in Cogstate scores was observed for either drug.

Excluded studies

The three studies excluded were meeting abstracts. Efforts to find further data on these studies in other publication formats were unsuccessful (Citrome et al., 2015a; Citrome et al., 2015b; Citrome et al., 2016b).

Risk of bias in included studies

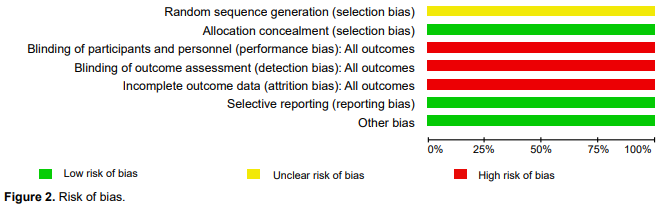

Allocation: Low risk of bias. Patients were randomized 2:1 to receive brexpiprazole or aripiprazole. Randomization was performed using the interactive voice response system or the interactive web response system (Figure 2).

Blinding: This was an open-label trial.

Incomplete outcome data: High risk of bias, although the authors indicated that there was a loss of data and provided the number of patients who reached the end of the trial. The data for the analysis included a full sample with imputed data, without a sensitivity analyses.

The review authors checked the clinical trial register to reduce selective reporting.

Other potential sources of bias: Sequence Generation. Unclear risk of bias. Patients were enrolled and randomized (2:1) to target doses of 3 mg/day, open-label brexpiprazole 3 mg/day, or aripiprazole. Unequal allocation can be scientifically advantageous and consistent with ethical study design. First, it may have substantial advantages in early phase trials, when the aim of investigation is to explore treatment dimensions. A second circumstance where uneven allocation may be justified is when study treatments are extremely costly. The need for additional safety information may also justify unequal allocation. Researchers often justify the use of unequal allocation in 2-armed confirmatory trials by appealing to patient demand or recruitment facility. However, the authors did not provide a rationale for this type of randomization.

Primary outcomes

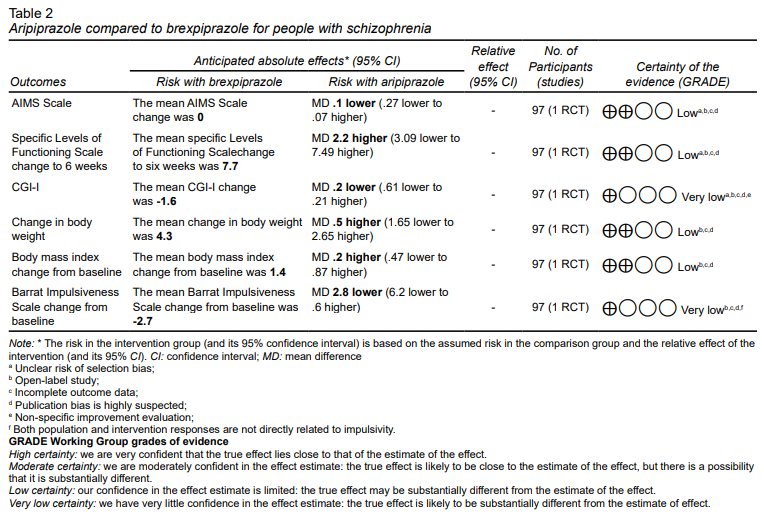

The PANSS scale rating and Cognitive Test Battery composite score were not eligible as primary outcomes for inclusion because only the least squares changes were reported (Table 2).

No significant differences were found between the CGI-I scores of brexpiprazole compared to aripiprazole (MD -.20, 95% CI ‐.61 to .21; very low‐certainty evidence). We found that aripiprazole may result in only a slight, non-significant difference in SLOF scores (MD 2.20, 95% CI -3.09 to 7.49; low‐certainty evidence).

Concerning the presentation of extrapyramidal side effects, no differences were detected on the AIMS scale (MD -.10, 95% CI -.27 to .07; low‐certainty evidence). No differences in body weight (MD .50, 95% IC-1.65 to 2.65; low‐certainty evidence) or body mass index changes (MD .20, 95% CI -.47 to .87; low‐certainty evidence) were detected regarding metabolic effects either.

Secondary outcomes

A small difference was observed in the Barrat impulsivity scale change, which could be marginally relevant, suggesting that brexpiprazole could be better for reducing impulsivity (MD -2.80, 95% IC -6.20, .60, low‐certainty evidence).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

We found only one study eligible for inclusion in this review. This was a 2‐arm parallel‐group in open-label trial with brexpiprazole 3mg/day or aripiprazole 15mg/day for six weeks in patients with schizophrenia.

We considered the evidence for all outcomes to be of low or very low certainty using the GRADE criteria for the scales used by the authors of the selected study. We found a low level of evidence for the following results: AIMS scale, Specific Levels of Functioning Scale Change to six weeks. We found a similarly low level of evidence for change in body weight, change in body mass index from baseline, and very low evidence with the CGI-I scale and Barrat Impulsiveness scale change from baseline.

The main difficulties in identifying the evidence on the interventions involve the biases found in the study including sequence generation, blinding of participants, blinding of outcome assessors, and incomplete outcomes. Biases with a lower risk of occurrence are selection bias, and reporting bias. Performance bias, detection bias, and attrition bias have a high risk of bias, and unclear risk of bias sequence generation The first two (selection bias and information bias) and the second two (selection bias and information bias) were low risk. Patients with a composite score greater than -.5 at baseline were randomized equally to each treatment group. Randomization was performed using the Voice/Web Response System, which can be accessed via telephone or the Internet, and the authors reported data for the prespecified outcomes. This bias was minimized by reviewing the clinical trial registry to minimize selective reporting.

The risk of bias was increased because it was an open-label study and the allocation, although randomized, was not blinded, which decreases the statistical power of the results. On the other hand, the authors indicated that there was a loss of data and provided the number of patients who reached the end of the trial. However, in their analysis of the data, they included the full sample with imputed data, without sensitivity analysis or excluding the missing data from the final analysis.

The risk of bias in the sequence generation was unclear because patients were enrolled and randomized (2:1) to target doses of brexpiprazole 3 mg/day or aripiprazole in the open-label study.

Sequence Generation. Unclear risk of bias. Patients were enrolled and randomized (2:1) to target doses of open- label brexpiprazole 3 mg/day or aripiprazole. Unequal allocation can be scientifically advantageous. First, it may have substantial advantages in early phase trials where the goal of the research is to explore treatment dimensions. A second circumstance in which unequal allocation may be justified is when the study treatments are particularly costlyHey & Kimmelman (2014). However, the authors did not justify this type of randomization.

According to the results of the included study, the improvement in the total PANSS scale between the two interventions was comparable and significant at six weeks of treatment, without establishing the superiority of one drug over the other. Interestingly, a systematic review and meta-analysis networkKishi et al., (2020) found a very similar response rate between aripiprazole and brexpiprazole, which were superior to placebo. Another systemic reviewHuhn el at. (2019), compared the efficacy and tolerability of thirty-two antipsychotics (including aripiprazole and brexpiprazole) orally for the acute treatment of subjects with multi-episode schizophrenia. It found improvement in total symptoms and positive symptoms for both when compared to placebo. Likewise, Aripiprazole was among the five antipsychotics that reported improvement in quality of life, while brexpiprazole achieved a favorable change in psychosocial functioning.

For our revision, no differences were observed in the cognitive functioning with any of the antipsychotics. Mean changes in abnormal movement assessment scales were not clinically relevant for any of the interventions, nor were changes in prolactin or metabolic parameters. For our revision, no differences were observed in the cognitive functioning with any of the antipsychotics. Mean changes in abnormal movement assessment scales were not clinically relevant for any interventions, nor were changes in prolactin or metabolic parameters. Similarly,Kishi et al., (2020) reported a low incidence of adverse effects leading to discontinuation (akathisia, extrapyramidal symptoms), compared to placebo. However, their study reported a higher incidence of weight gain with both antipsychotics. Another reviewHuhn el at. (2019) also highlights brexpiprazole for its positive response rate and aripiprazole for the lower incidence of antiparkinson drug usage to treat extrapyramidal effects.

Regarding the economic advantages of both antipsychotics, aripiprazole and brexpiprazole, several factors should be considered. These include cost, their existence within the basic tables of health institutions and hospitals and the overall economic impact on the care of side effects and treatment adherence. It is also necessary to examine the role some may have in the effect on the symptomatic dimensions of schizophrenia responsible for long-term disability that interfere with psychosocial functioning (negative symptoms and cognitive symptoms).

Aripiprazole is usually available as a generic drug, which generally significantly reduces its cost compared to patent drugs. As it has been available for a longer period, knowledge of both specialists (experience in use) and aripiprazole may be more widely available.

Brexpiprazole is a newer drug with no generic options as yet, significantly increasing its cost. If it demonstrates a better tolerability profile, this could translate into reduced side effect care costs, better treatment adherence and less need for additional medication (correctors). If it translates into a better overall or specific response to the positive, negative, affective, and cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia, it could improve patients’ functioning and quality of life, including less need for additional medication (correctors). If it translates into a better overall or specific response to the positive, negative, affective, and cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia, it could improve patients’ functioning and quality of life. This would include fewer relapses and cost savings in hospitalizations and scheduled office or emergency department visits.

The result of this review has several significant limitations as it is limited to a single study that is not even a controlled clinical trial. It also has important biases, as described in the discussion. It is therefore not possible to establish a recommendation for the prescription of one of the antipsychotics in the study over the other.

There remains ample room for further research on this topic, as results and evidence from ongoing studies can be incorporated, particularly in this group of drugs that have been proposed in the literature as a third generation of antipsychotics due to their unique pharmacological profile.

More research is required to highlight the differences between both drugs that appear to be similar, to justify the high cost of one over the other, particularly in developing countries.

Several research topics may be explored, both when comparing aripiprazole with other second-generation antipsychotics and in broader contexts. Brexpiprazole and aripiprazole have been proposed as prototype third-generation drugs. It would be worth exploring this line and determining whether they really deserve to be characterized as such, due to their different mechanism of action.