INTRODUCTION

Transgender is a term used for gender diverse individuals, whose assigned sex/gender at birth differs from their current gender identity, gender expression, or behavior (American Psychological Association, 2015). It encompasses a wide range of people such as transsexuals (those seeking to change their sex to the gender with which they identify, using hormone and/or surgical treatment). It also includes trans or gender non-conforming people (those who adapt their body to the gender with which they identify with slight medical intervention [hormone therapy]). In addition, it comprises cross-dressers (those who change their gender temporarily using external signs such as clothing and makeup;Carrera-Fernández et al., 2014).

Most studies on attitudes toward transgender people have shown that this group is still far from being fully accepted by society (Carrera-Fernández et al., 2014). Its members are often victims of multiple types of violence across several areas of life due to stigma and society’s intolerance of gender non-conformity (Bockting, 2014; Bradford et al., 2013; Cruz, 2014; D’Augelli et al., 2003; Robles et al., 2016; Grossman & D’Augelli, 2006; Grossman et al., 2011; Henning-Stout & James, 2000; Kosenko et al., 2013; Lombardi et al., 2002; Robles et al., 2016; Stotzer, 2009).

According to the literature, anti-trans prejudice and hate against trans people includes three key constructs: transphobia, genderism, and gender-bashing (Hill, 2003; Hill & Willoughby, 2005). Transphobia comprises negative beliefs and attitudes about transgender people, expressed through violence (physical, sexual, or verbal), harassment, discrimination, and prejudice toward this group (Herbst et al., 2007). Like homophobia and homonegativity, transphobia is based on emotional disgust, irrational fear, hatred, or intolerance toward individuals who do not conform to society’s gender/sex expectations (Hill & Willoughby, 2005). However, thransphobia differs from homophobia as it focus on broader issues such as gender roles and gender identities (Nagoshi et al., 2008).

Genderism is a broad negative cultural ideology perpetuating negative judgments and reinforcing the negative evaluation of gender non-conformity or incongruence between sex and gender. Genderists believe that those who do not conform to socio-cultural expectations of gender are pathological. Genderism is a type of social oppression that can be forced on individuals and often leads to internalized psychological shame. Gender-bashing refers to fear expressed in acts of violence, assault, and/or harassment towards people who do not conform to gender norms or sociocultural expectations. Genderism is therefore the overarching negative cultural ideology, transphobia is emotional disgust and fear, while gender-bashing is fear expressed through acts of violence (Hill, 2003; Hill & Willoughby, 2005).

Transphobia is a social problem that systematically and unfairly exposes transgender people to exclusion, repression, and other forms of personal, institutional, and social harassment (Galupo et al., 2014; Joel et al., 2014; Whitfield et al., 2019). All these forms of discriminatory social actions are so widespread that transgenderism has become a pathological condition that is stigmatized and sanctioned (Alonso-Martínez et al., 2021; Haley et al., 2019; Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Páez et al., 2015). This, in turn, causes psychosocial, health, and mental health problems in transgender people globally (Lo & Horton, 2016), particularly in low- and middle-income contexts (Bazargan & Galvan, 2012; Bockting, 2014; Bradford et al., 2013; Cruz, 2014; Kenagy, 2005; Lombardi et al., 2002; Martínez-Guzmán & Johnson, 2021; Melendez & Pinto, 2007). According to Transgender Europe and the International Report of the Transgender Murder Monitoring Project (Bautista et al., 2018), Mexico is the second most dangerous country in the world after Brazil for transgender since it has the highest rate of transphobic hate crime and impunity (Grant, 2021).

The multiple forms of violence affecting transgender people, particularly transgender women, are rooted in both structural and sociocultural factors associated with the hetero-patriarchal system and the cultural norm ofmachismopermeating Mexican society. These factors define rigid gender roles, reflect heteronormative expectations of male behavior, contribute to the reproduction of male domination, and maintain social structures that justify the exercise of gender violence. They begin in the family and extend to multiple social contexts (Constant, 2017; Verduzco et al., 2011; Steffens et al., 2014; da Espinosa et al., 2020).

Despite the severity of the problem, studies on transphobia in Mexico remain scarce. Further research is required to explore the intolerance and prejudice that give rise to the transphobia phenomenon in the Mexican population, to expand our understanding of the causes of violent attitudes toward gender non-conforming. It is also necessary obtain evidence to develop awareness campaigns, strategies, and interventions to improve transgender acceptance, eliminate the prejudice that leads to violent attitudes and promote inclusive environments for the transgender population.

The aim of the present study was therefore to analyze sex differences in transphobic attitudes toward transgender people. Based on previous studies (Carrera-Fernández et al., 2014; Chen & Anderson et al., 2017; Costa & Davies, 2012; Nagoshi et al., 2008), and given the predominance of the hetero-patriarchal andmachista phenomenon in Mexican society, we expected men to have more transphobic attitudes than women.

METHOD

Study design and participants

This is a cross-sectional, internet-based study.

Subjects

The present study included adult Mexican participants from the general population residing in Mexico, recruited by a convenience sample approach. Inclusion criteria were being between 18 and 75 years of age and having an electronic device to answer the survey.

Procedure

The sample was recruited from November 2019 to March 2020. Participants were mexican adults who were invited by social networks (Facebook & WhatApp) to complete an anonymous online survey designed using Qualtrics®, containing the Genderism and Transphobia Scale-Revised-Short Form (GTS-R-SF,Tebbe et al., 2014). The aims and procedures were explained at the beginning of the survey, and participants who voluntarily agreed to participate gave their informed consent before answering the survey. Participants did not receive any incentive or remuneration for their participation in the study.

Measurement

After providing their informed consent, participants first answered questions on socio-demographic variables (such as age, sex, educational achievement, marital status, and current working activities) and subsequently completed the GTS-R-SF.

The GTS-R-SF is a self-administered scale with 13 items, each rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 7 (strongly disagree). In keeping with the study byHill & Willoughby (2005), all items are reverse scored except for item 2 (“If a friend wanted to have his penis removed to become a woman, I would openly support him”). Higher total scores indicate greater anti-trans prejudice. This scale covers two main domains: genderism/transphobia (eight items) and gender-bashing (five item) (Tebbe et al., 2014). The genderism/transphobia dimension assesses negative cognitions about gender non-conformity and negative emotional reactions toward trans individuals reflected in negative anti-trans statements.The gender- bashing dimension assesses the propensity for behavioral violence toward trans people (Hill & Willoughby, 2005).

The Spanish version of the GTS-R-SF was used in the present study (Domínguez & Fresán, 2022).For this version, the original scale ofTebbe et al. (2014) was translated into Spanish based on recommendations by American Research Teams (US Census Bureau, 2010).It was reviewed by two independent health professional experts in the care and treatment of transgender people and a pilot study was undertaken to ensure that all items were clear and comprehensible to people in the community (n = 40). Finally, internal reliability for the present sample was determined using the Composite Reliability Index (CRI) (genderism/transphobia CRI = .91, gender bashing CRI = .72, total CRI = .85).

Statistical analysis

Frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means, standard deviations (SD), and ranges were used for descriptive purposes. The 21.0 version of the SPSS statistical software was used for all analyses. Demographic features and the GTS-R-SF dimensions and total scores were compared using contingency table chi-squared tests (χ2) and independent samplest-tests. The effect size was calculated for the significant results obtained in the chi-squared tests (Cramer’sV) and the independent samples t-tests (Cohen d), with values being interpreted as small (.1 – .3), medium (.4 – .7), and large (> .8). All analyses used SPSS version 21.0, with significance set atp < .05.

Ethical considerations

All study procedures and materials were performed in keeping with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics and Research Committees of the Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz National Institute of Psychiatry in Mexico City (reference number: CONBIOETICA-09-CEI-01020170316).

RESULTS

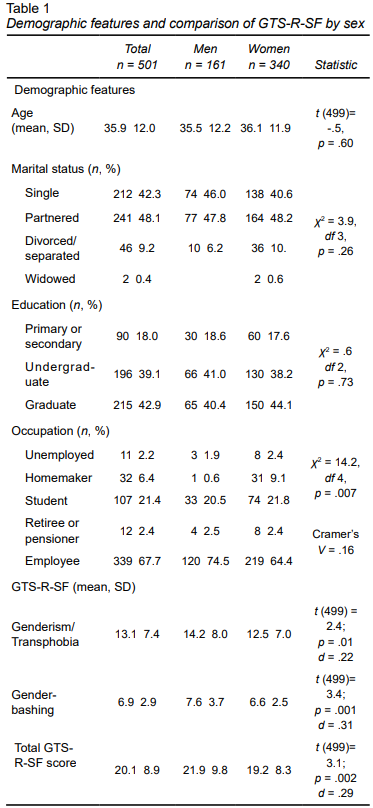

A total of 501 Mexican adults (> 18 years old) drawn from the general population and currently living in Mexico participated in the study. Approximately two-thirds of the 501 participants were women (67.9%, n = 340). The mean age of the sample was 36.0 years (SD = 12.0, range 18-73), and over two-thirds were engaged in paid employment (67.7%, n = 339). All participants were from urban areas in twenty-five out of the thirty-two states in Mexico, although most were from Mexico City (63.5%, n = 318). The remaining demographic features are displayed in Table 1. No differences emerged between men and women in terms of sociodemographic features, except for occupation, where a higher proportion of women were engaged in household activities and more men in paid employment.

Findings from the comparison of GTS-R-SF dimensions between men and women showed that male participants exhibited significantly higher scores than women in both the genderism and transphobia and gender bashing dimensions as well as the total GTS-R-SF score (Table 1).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Consistent with studies from other countries, findings on differences by sex in GTS-R-SF showed that men exhibit more trans-prejudice and are less accepting of gender-nonconforming people than women (Antoszewski et al., 2007; Carrera-Fernández et al., 2014; Chen & Anderson, 2017; Costa & Davies, 2012; Hill & Willoughby, 2005; Landen & Innala, 2000; Nagoshi et al., 2008; Winter et al., 2007,2008). This phenomenon is rooted in both structural and sociocultural factors linked to the hetero-patriarchal system and themachismo culture predominant in Mexican society. It reflects heteronormative expectations of male behavior, contributes to the promotion of the superiority and domination of men over women, defines rigid gender roles, and maintains social structures justifying the exercise of gender violence in multiple social contexts (Constant, 2017; Verduzco et al., 2011; Steffens et al., 2014; Espinosa et al., 2020). Our findings contrast with those ofGorrotxategi et al., 2020), conducted on Spanish university students of social education (mean age of 20 years), who reported higher mean scores in the dimensions of the GTS-R-SF scale in both men (transphobia/genderism = 38.9 vs 14.2, and gender bashingg = 36.5 vs 7.6) and women (transphobia/genderism = 41.3 vs. 12.5, and gender bashing = 41.4 vs. 6.6). In the GTS-R-SF validation study, the mean scores of the transphobia/genderism and gender bashing dimensions were under four points (Tebbe et al., 2014). This shows that trans-prejudices are higher in our sample, possibly reflecting the cultural heteronormative expectations of Mexican culture. These studies included university students (n = 64;Gorrotxategi et al., 2020) and undergraduate students (n = 314;Tebbe et al., 2014) aged 18 to 35, which differs from the mean age of our participants (age range 18-75 years). One possible explanation for these differences is the current change in the interpretation of gender and sexuality observed in younger generations (Gorrotxategi et al., 2020). Extreme anti-trans prejudices (like those assessed with the GTS-R-SF) are less common and even opposed to the values of these new generations. However, this should be further studied in similar samples.

Some authors have also argued that the high prevalence of transphobia among men is influenced by traditional male identity based on misogyny and homophobia. Men’s prejudice and discrimination toward transgender people appear to be used as a means of reaffirming and preserving their masculinity and heterosexuality (Carrera-Fernández et al., 2014; Kimmel, 1994). Moreover, findings support the fact that men strive more than women to adhere to gender rules and are likely to feel more threatened than women by transgender people. This is due to the conservative beliefs of the cis-normative system and the irrational fear and hatred of those who do not fit the dominant gender categories and challenge traditional social and familial norms and roles (Burnes et al., 2010; Alonso-Martínez et al., 2021; Vandello et al., 2008).

Transphobia is a social problem that systematically and unfairly exposes transgender people to exclusion, repression, and other forms of personal, institutional, and social harassment (Galupo et al., 2014; Joel et al., 2014; Whitfield et al., 2019). These discriminatory actions are so widespread that transgender has become a pathological condition that is stigmatized and sanctioned, leading to destructive behaviors and discriminatory actions that threaten their human rights (Alonso-Martínez et al., 2021; Haley et al., 2019; Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Páez et al., 2015). These experiences of rejection and violence cause significant personal suffering that can negatively impact transgender physical and mental health, making it necessary to develop and implement awareness campaigns, anti-discrimination policies, and legislative actions. This will reduce transphobia and guarantee social inclusion in all sectors based on human rights and social justice, expand the rights of transgender people and provide greater protection from discrimination and social rejection (Stieglitz, 2010).

The current research has certain limitations that should be considered when interpreting results. First, our sample had high educational attainment and were from urban areas of the country, which is not representative of the Mexican population, characterized by low educational attainment and diverse cultural backgrounds when rural populations are included. Future studies should examine our results in other Mexican settings with larger, more diverse samples to compare research findings across cultures. This would also make it possible to identify groups that would benefit from interventions focused on the transformation of social attitudes into the acceptance of gender diversity and the reduction of anti-trans prejudice (Páez et al., 2015; Clark & Hughto et al., 2019).